A playbook for design to dev handoff

The real user experience happens in code. Here's how to be a part of designing it, and how AI can help

Henry Dan

Oct 14, 2025

The real user experience happens in code, not Figma.

You can spend as much time as you want designing pixel perfect screens and idealized user flows, but if your great ideas don't make it into code your users will never know.

A lot of designers will throw their designs over the wall and hope developers figure it out. But the designers who understand more about development to collaborate effectively are the ones shipping better products, faster.

I'm not saying you need to be an expert developer to design great experiences, you just need to speak their language well enough to be a true collaborator instead of a bottleneck.

This guide will show you how to bridge that gap, from specific tips on where to get started to AI tools you can use to write more code yourself. The goal is to build the kind of designer-developer partnership that leads to exceptional products and deepens your impact as a designer.

Who cares?

Why do I have to learn about development? Can't developers just learn design, or better yet just do what I tell them?

The best solutions are desirable AND feasible. When you can understand and design based on technical constraints, you're part of the solution instead of creating problems for developers to solve after the fact. The goal is to be in charge of the compromise yourself, instead of making someone else make that call.

So, do I need to learn to code?

Well, yes and no.

You need to learn about code, but you don’t need to worry about becoming a full stack developer. Here’s what I recommend:

Minimum tier: learn HTML and CSS. You should be able to build the websites you design. The bad news is this isn't optional anymore. The good news is, it's easier than it's ever been to learn. Start using Framer and build an understanding of how layouts and styles are described in code. It’s just as easy to use as Figma, but it’s production-ready.

Mid tier: Build enough technical knowledge to speak the same language. You need to understand roughly what it takes to build what you're designing so you can collaborate instead of just handing things off and hoping for the best.

Top tier: Build towards being a design engineer. Being able to prototype your own ideas in code and even ship code to production is the best way to become insanely hirable and very unfireable as a designer. It also means you have more of a say in what the end user experience looks like, and more agency when it comes to fixing problems.

The more you know the wider range of projects you can work on, and the more people you can work well with. Building your own ideas or being able to communicate with the person who is is mission-critical to bringing your designs to life.

Where do I start?

Bring Developers Into the Conversation Early. Share work in progress, and ask them to point out red flags and questions about the implementation. These problems are easier to solve early when there’s a dialogue, so invite them into the conversation to get their input.

Stick around after handoff. Sending the Figma link is just the start of implementation, and there’s a million surprises that can happen in the translation from design to code. So check in with your devs, see how things are going, and if there are questions you can answer or changes you can make to simplify the designs. Think of it as a gradual transition where your role ramps down as development ramps up, with neither one hitting zero.

Use AI to help with learning and practice. Use Lovable to build a really simple app, and pick through the code to see how it works and how to make changes. AI can help explain code snippets and architecture, and running into bugs and constraints is a great way to learn.

Learn your company’s design system. Components in code are probably very different from your Figma library, so take a step out of your comfort zone and go to the source. Does your button component have primary, secondary, tertiary styles? Or is it filled, outline, ghost? Maybe you call your select input a dropdown when it’s really a combobox. Knowing what this library looks like will help you a) design based on what exists and b) be more intentional about when you want to add a custom component.

These are the basics, and are a fantastic starting point to be more collaborative with your dev team.

Ready to deeper dive? Here are some other areas to get better at:

Writing handoff documentation

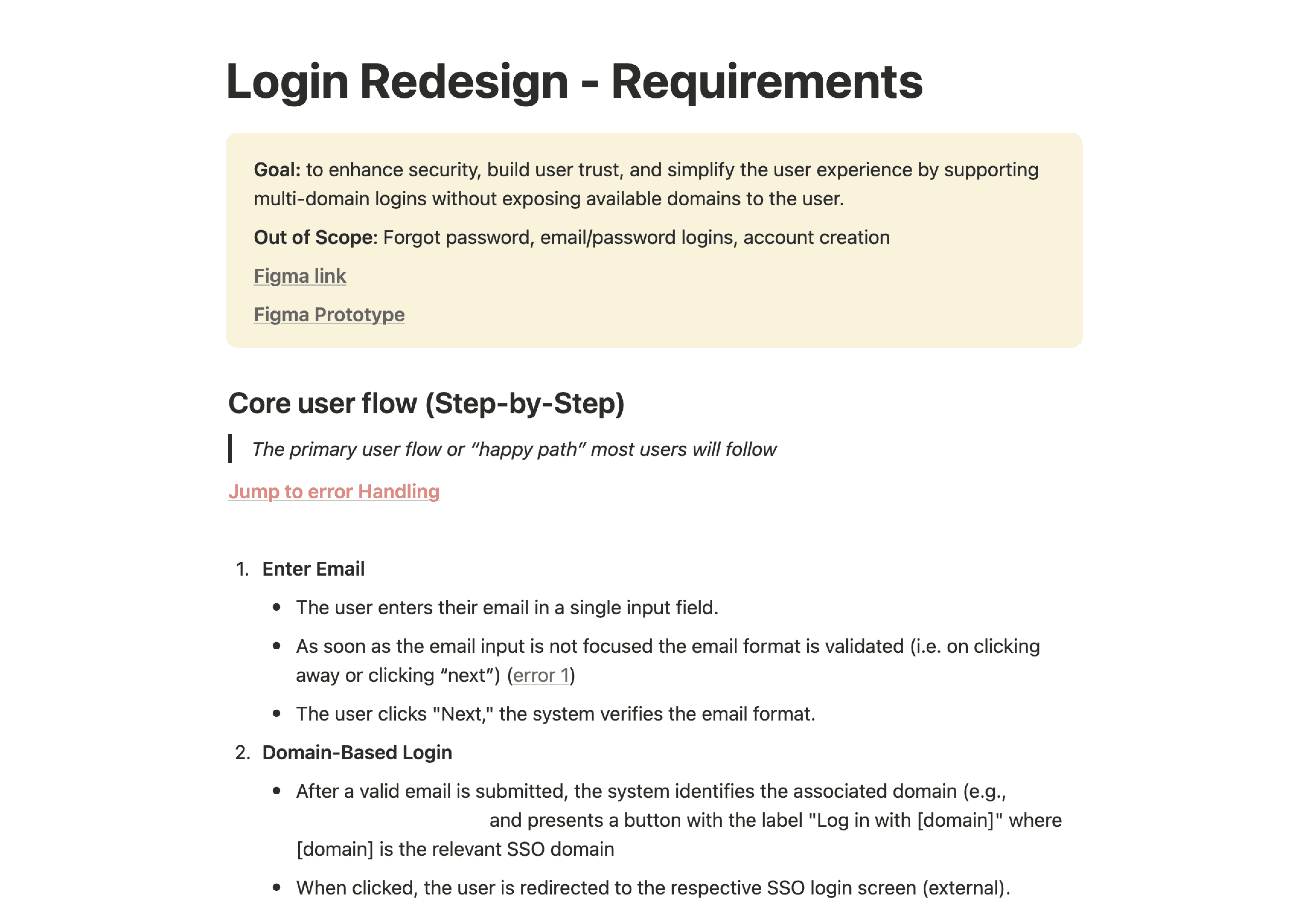

In a perfect world your Figma designs can speak for themselves. But this isn’t a perfect world, and products are complicated. Writing documentation can be a huge boost to communication during handoff.

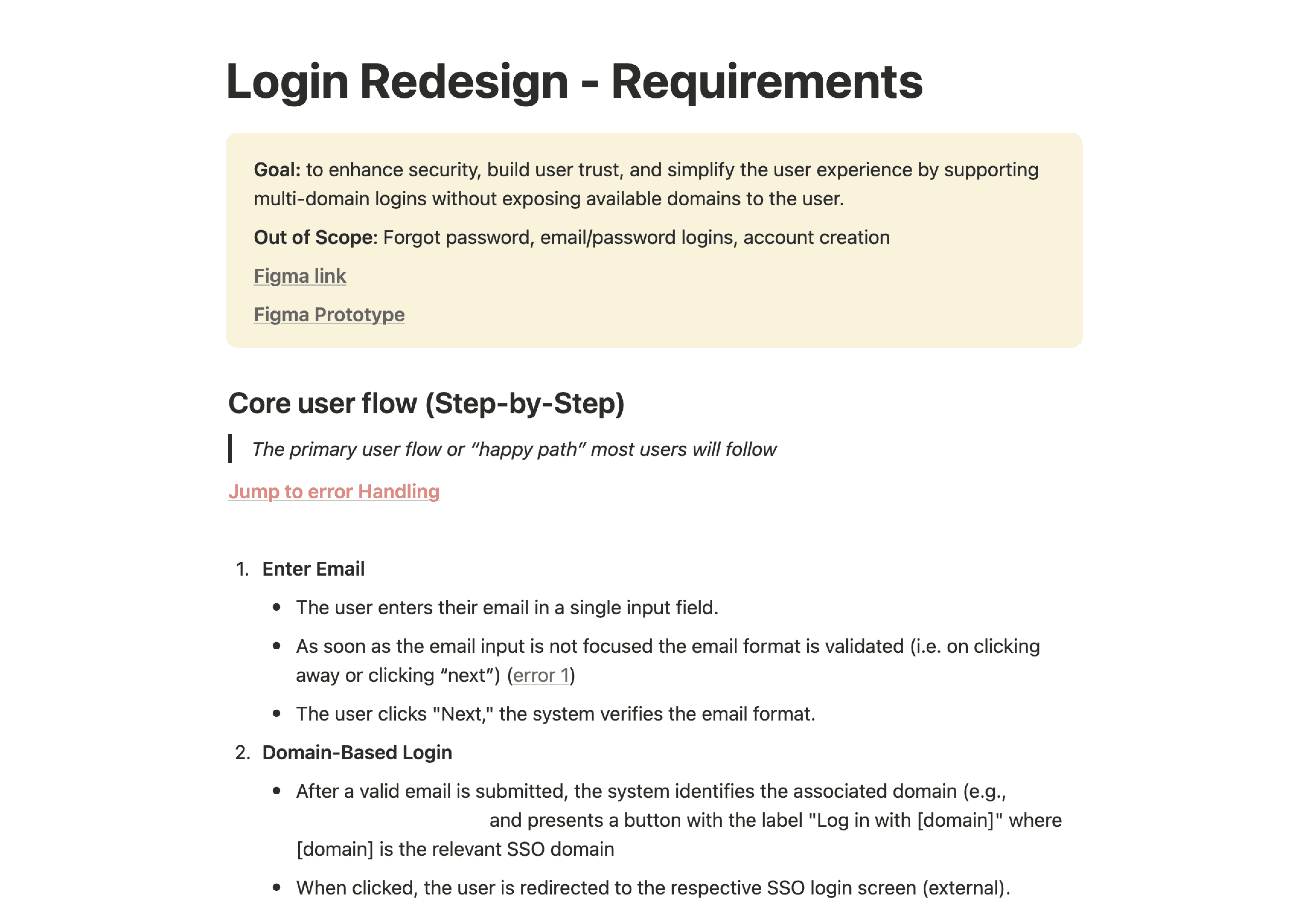

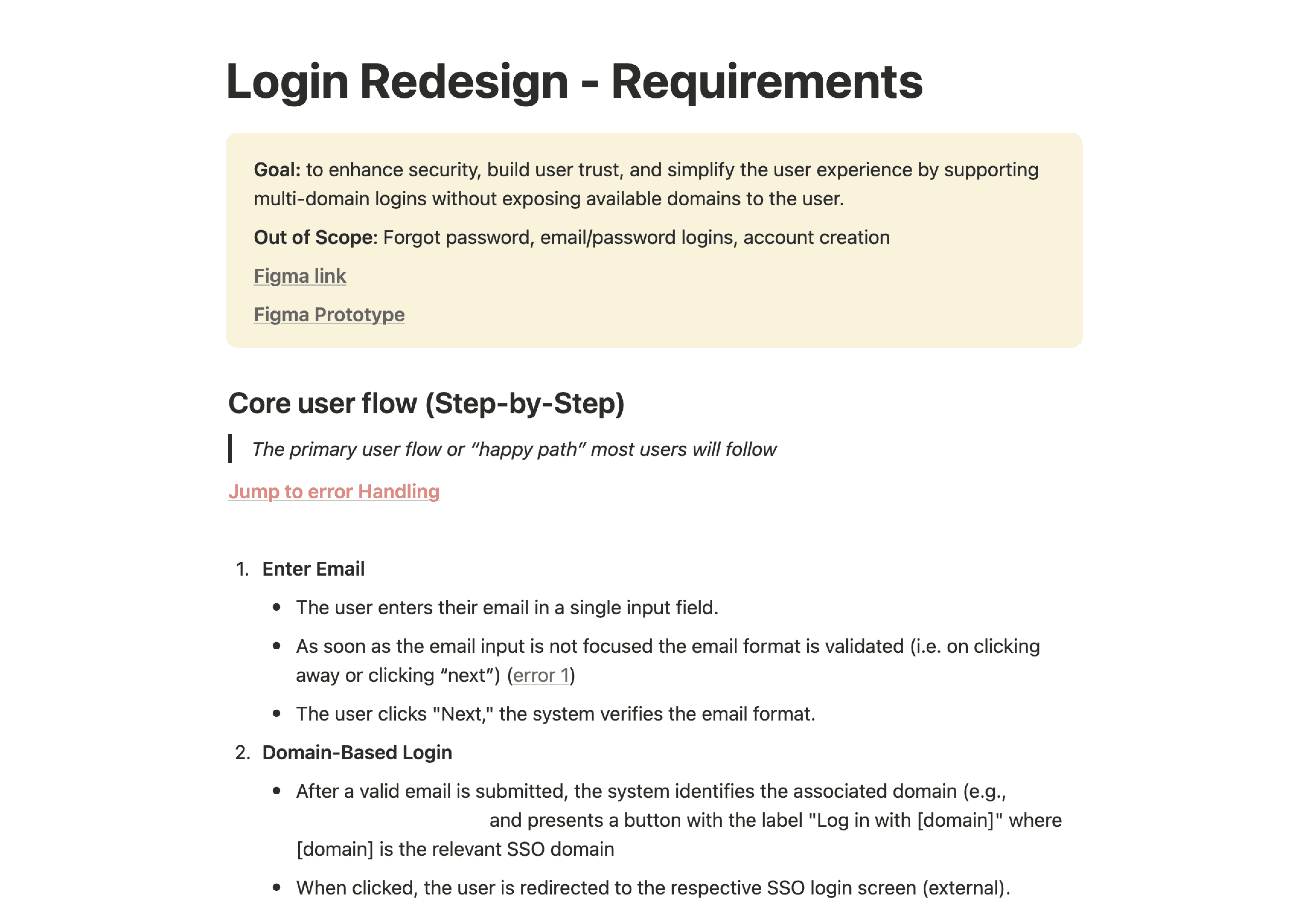

Your goal is to answer 80-90% of questions before development starts. There will always be surprises, but most questions should be preventable. Never hand-wave important details. Avoid hand-waving and saying “we’ll figure that out later”. Every vague detail creates confusion during implementation.

Write notes in context. Copy in Figjam post its to your design file and add notes in context next to the designs. If your developers have dev mode plans you can use figma’s built in annotation and markup tools.

Make it readable - don’t overdo it. Nobody wants to read a novel of text just to do their job. Quick notes and short Loom videos are best. If you have a lot to write make sure it’s organized and searchable, for example adding a linked table of contents in Notion or Google Docs to navigate around.

What should I document?

Try to cover everything that’s not clearly evident just by looking at the designs or clicking on the prototype.

Be specific about data sources and logic: Don't just show a list of users on a dashboard with a show more button, write something like: "Display first 10 users alphabetically. Show more displays the next 5 in the list.”

Define fallback behaviors: What happens when data is missing? "Show avatar if available, otherwise show initials with a randomized color from our brand palette."

Clarify edge cases: What happens when a user has a really long name? “Truncate text to a single line if it extends past the container.” What if there are zero items in this list? “Display this empty state if there are no search results.”

Specify scope clearly. This is a great dashboard design, but is it customizable or filterable? Are individual charts filterable? “Users can filter data and apply it to the entire dashboard and hide charts, but per-chart filtering is out of scope for now.”

Basically good document just means getting the important stuff out of your head, and tracking it somewhere so the devs can answer most of their questions quickly. And if anything else comes up you can focus your time on solving the big problems, not the boring little things.

Frontend Development

TL:DR; Front end code controls everything users can see and interact with directly in their browser, like layouts, buttons, animations, and forms.

The basics

Let’s start with the simplest possible explanation:

The basics of html/css. Hopefully you’ve had some experience playing around with simple HTML/CSS sites. If not, no worries:

HTML (the Blueprint) Its only job is to define and organize the content. It tells the browser, "This is a headline," "This is a paragraph," "This is an image," and "This is a list of links” to create a basic unstyled skeleton of the page.

CSS (the Designer) styles the content defined by HTML. It tells the browser, "Make all headlines dark blue and use a specific font," "Make all images have a rounded border," or "Arrange the links in a horizontal navigation bar."

The basics of React. Think of React as building a user interface with smart, reusable design components like interactive Lego bricks. It’s like a smarter, more dynamic version of your Figma component library.

React allows you to build a dynamic webpage out of individual components, instead of a static HTML/CSS file that is just a fixed document. Individual "components" (like a search bar, a user profile card, or a button) package their own HTML structure, CSS styles, and JavaScript logic together to make them easier to reuse.

React components have state (a built-in memory). They can remember things, like what a user has typed into a search field or whether a dropdown menu is open or closed, and automatically update the display when that "state" changes. This is what makes modern web apps feel so fast and dynamic.

There’s plenty more that I’m glossing over here, but this is the “in a nutshell” explanation.

How can I improve handoff?

So, what do you need to know about the world of frontend development?

Learn your company’s design system. Like we talked about before, code components are a different animal than Figma components. Knowing what components are available will let you plan your design intentionally around what’s possible today, versus what’s custom and will take more time. Talk to your devs, look at the code, or explore the documentation. If you’re using an existing library like MUI or Shadcn there is publicly available documentation. And for custom components your devs may have their own internal documentation in something like Storybook where you can explore the components.

Learn Framer for web development. Framer is a visual builder for websites that looks and feels just like Figma, but lets you create full functional websites using react. It’s a great way to practice designing within constraints while still having a familiar environment to explore.

Note there are also visual builders for react like Reweb and Plasmic. I haven’t used either of them, but it’s worth exploring.

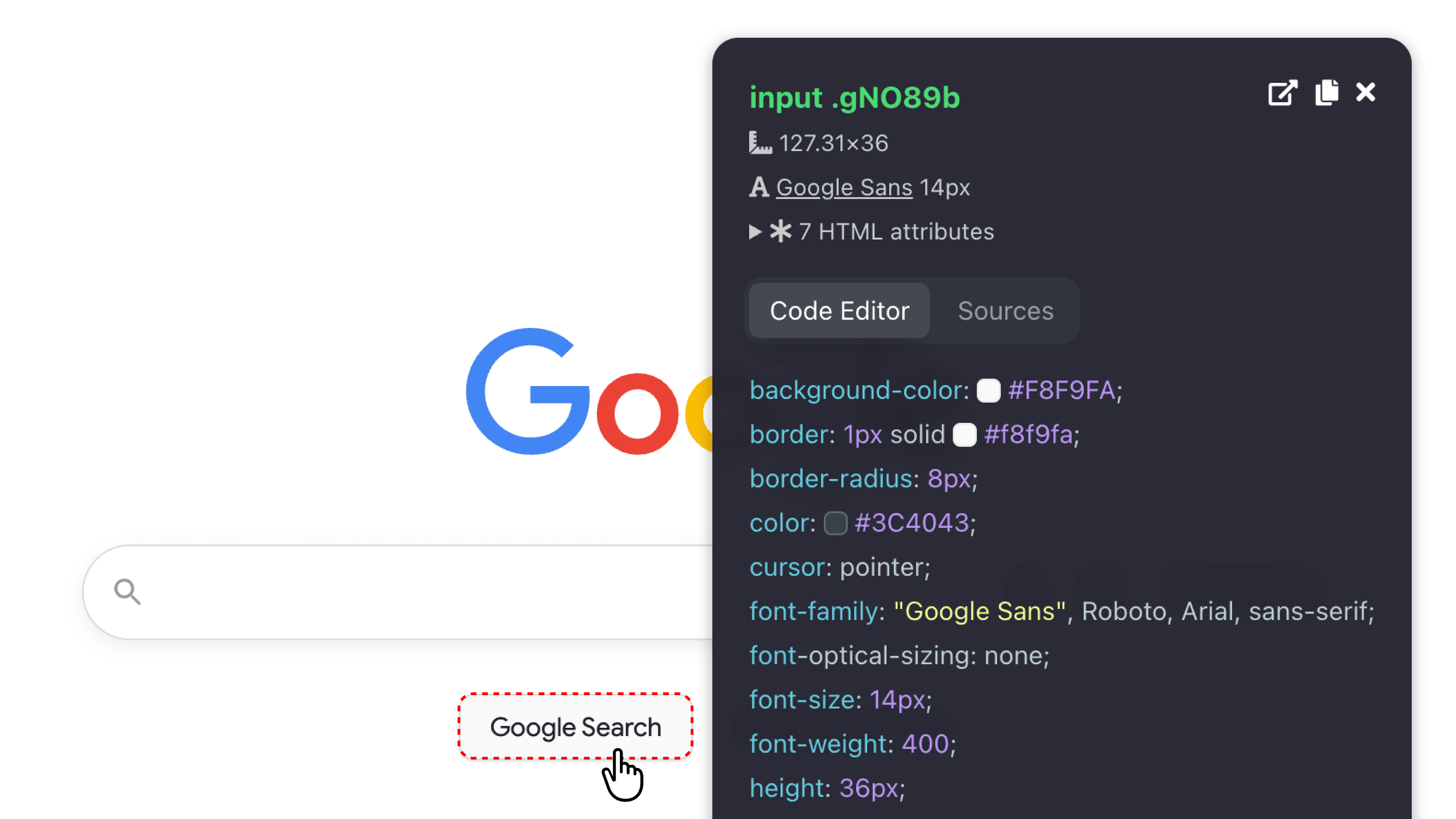

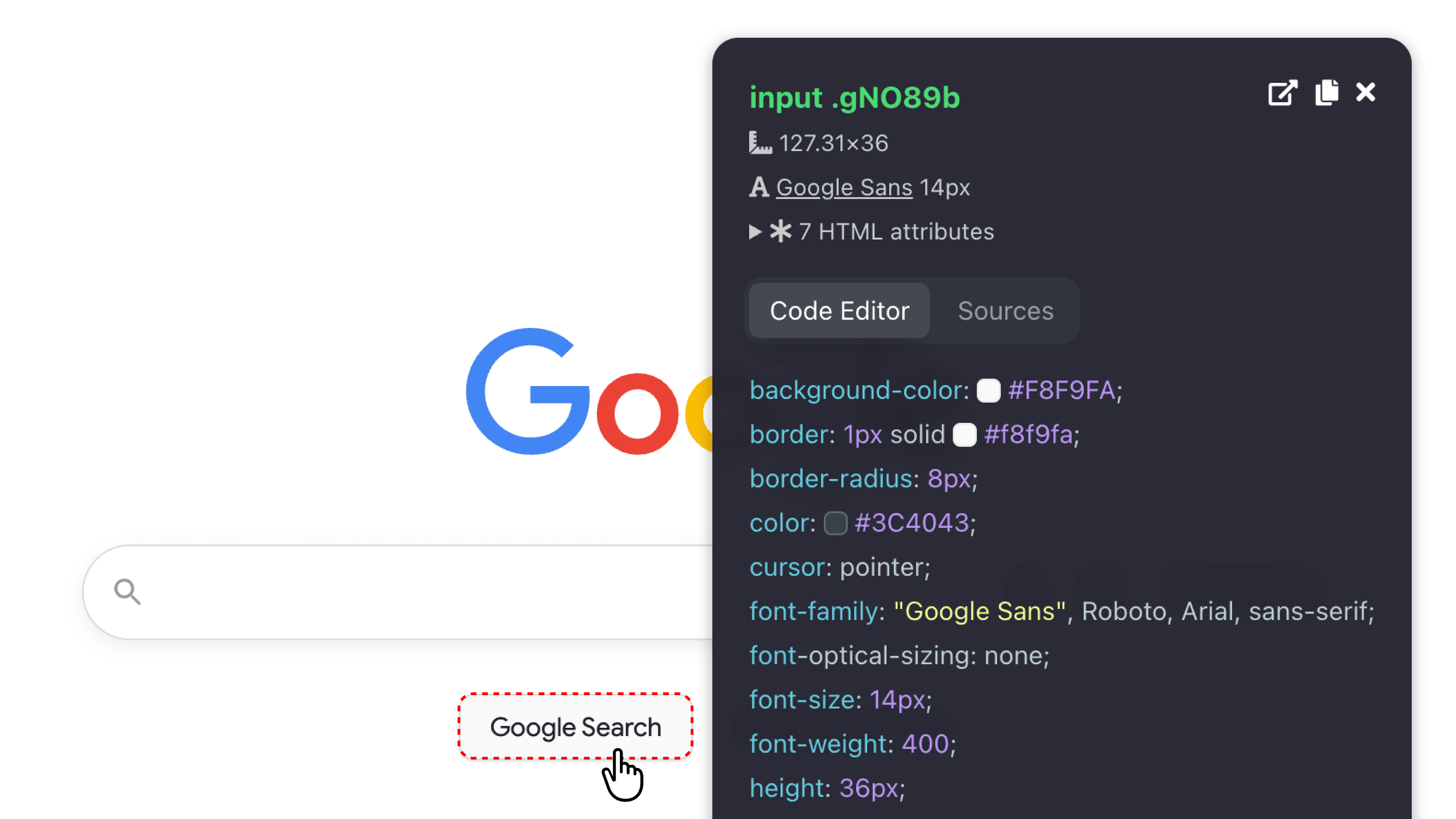

Get access to your team’s repo and explore. Even if you’re not pushing changes to production, it can be a huge help to just have read-only access your team’s code to poke around and see how things work. This is also a great gateway to making small design fixes in code, like fixing colors, border radius, or spacing issues.

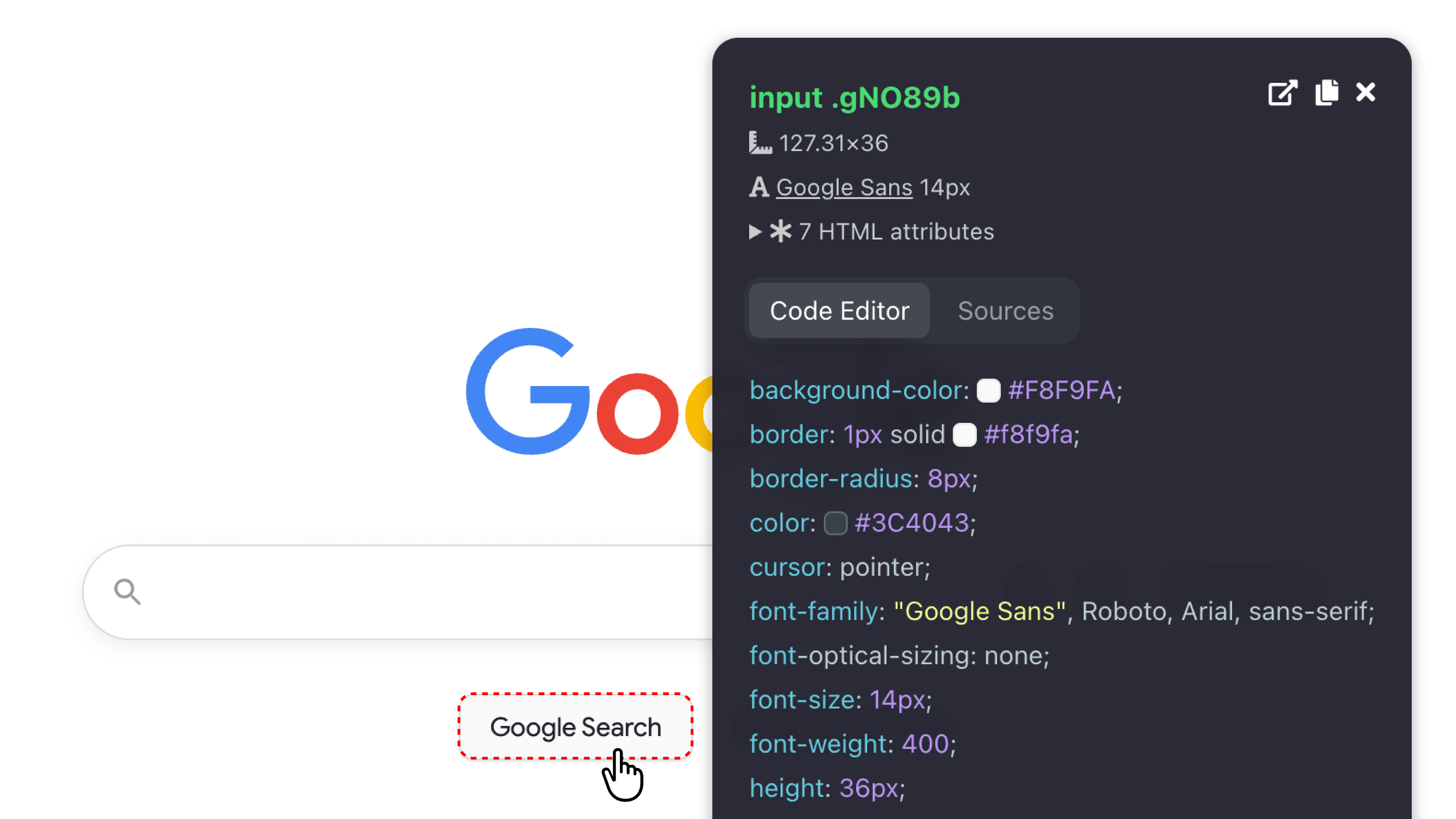

Use AI to explain code: You can use tools like Cursor or Claude code let you highlight code sections and ask for explanations that take into account the full context of your software. Or for small sections of code you can even just copy snippets into Chatgpt to get quick, easy to understand explanations.

You need to understand constraints, even if you can’t write code. When making design decisions you want to be able to plan through the lens of a developer. Will this be hard to implement? How will this UI adapt to changing data onscreen? How will it look on desktop vs. mobile? All of this will make your designs more effective.

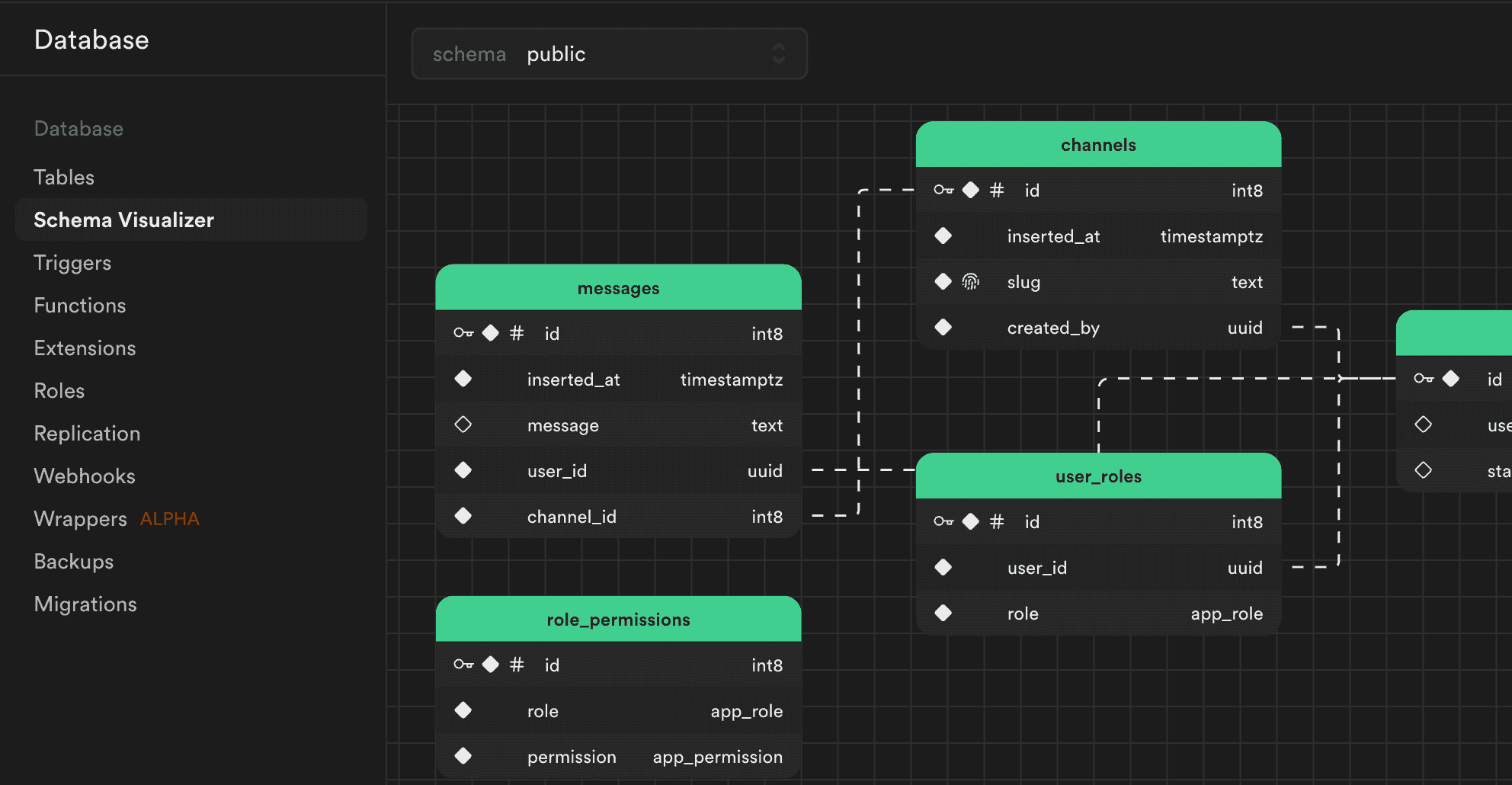

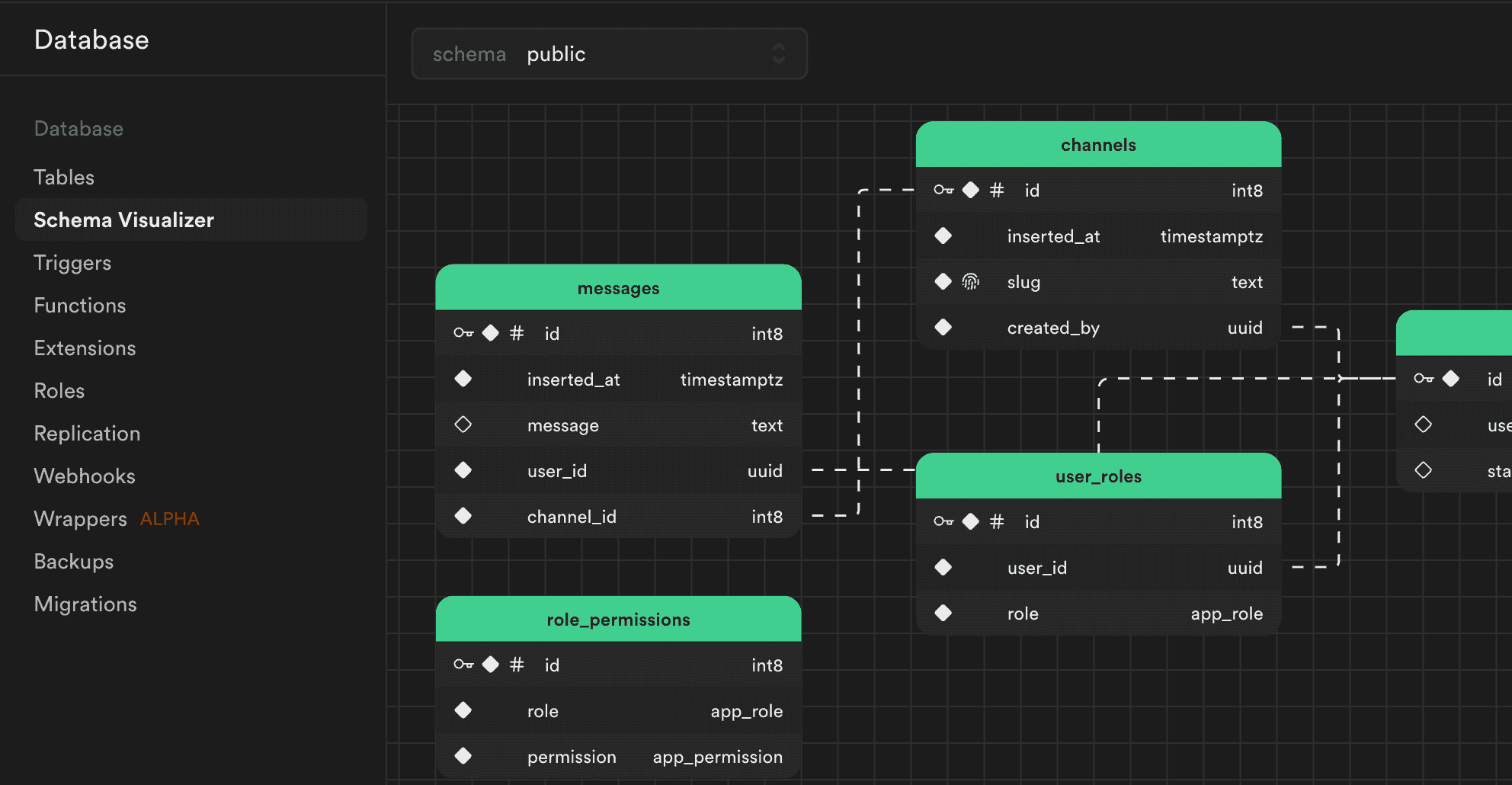

Backend Development (Super underrated)

Front end is the part of code you can see, back end is pretty much all of the data that powers it.

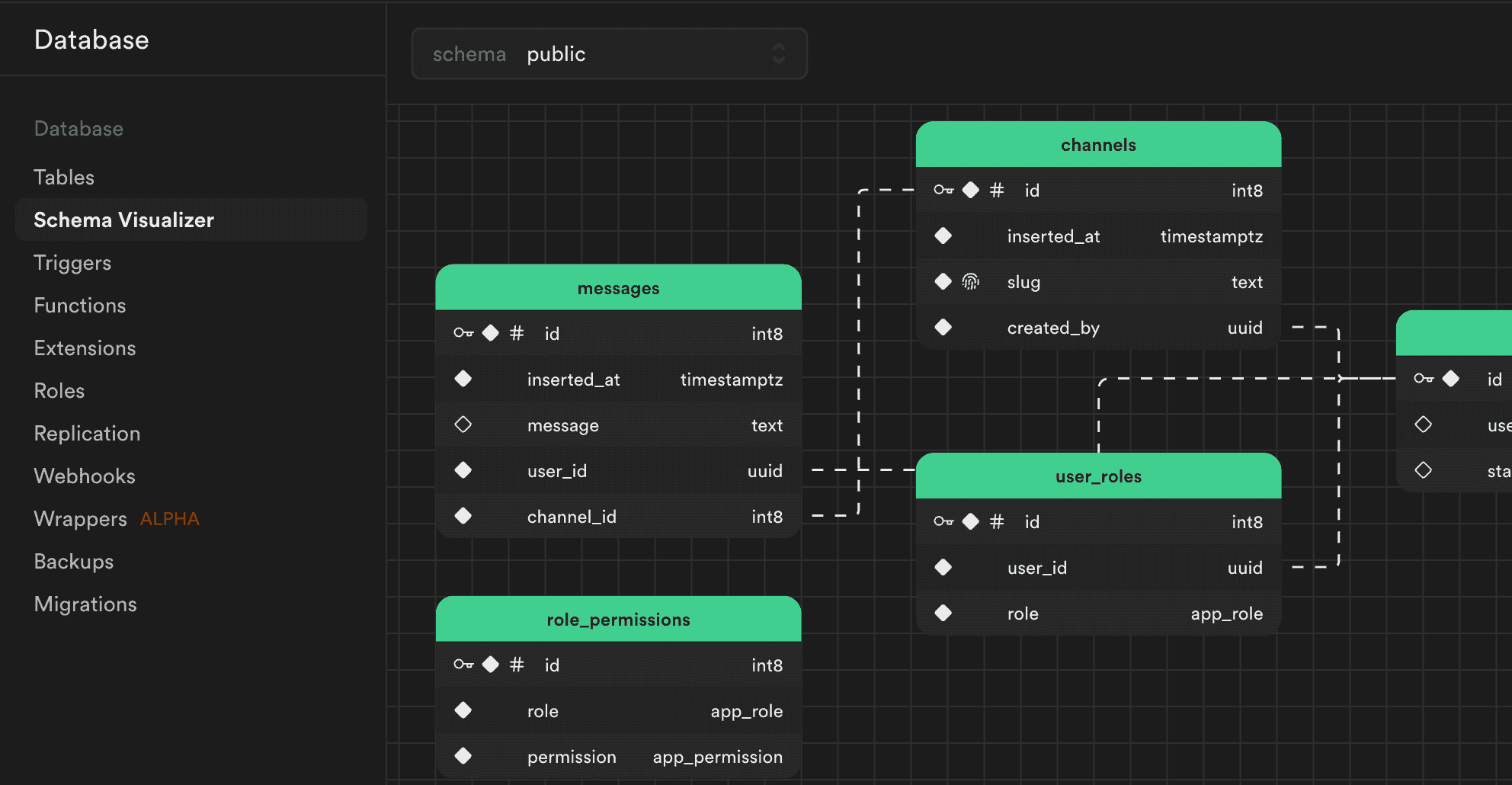

Basically every piece of information in your designs is powered by data on the backend, and understanding this will help make your designs more true to life.

The basics

Everything is data:

All of your users

Their preferences and saved information

Their account login information

Their permissions and roles (what different types of users see and can do in the app)

The documents, files, images or whatever things that they upload, create, or share in the app

The properties of those things (like the file name and type and when it was created)

The activities people do in the app that get tracked (i.e. if there’s a timeline of changes to a document)

Data can come from other sources via APIs (for example if addresses are auto completed with Google Maps data. You’re pulling that from Google, not storing all of it yourself)

All of this is tracked in a database and is constantly updated when changes are made. When you search for something and it’s loading that’s when the app is taking time to look through the database for the important data.

Picture a huge excel spreadsheet with all of the information needed to run your app.

That data has types

Numbers are numbers (they can be weird stuff like whole numbers or integers and stuff too)

A string is text (like a user’s name)

Boolean is true or false (like checkboxes)

Enum is a selection from a list of options (think select inputs or radio button lists)

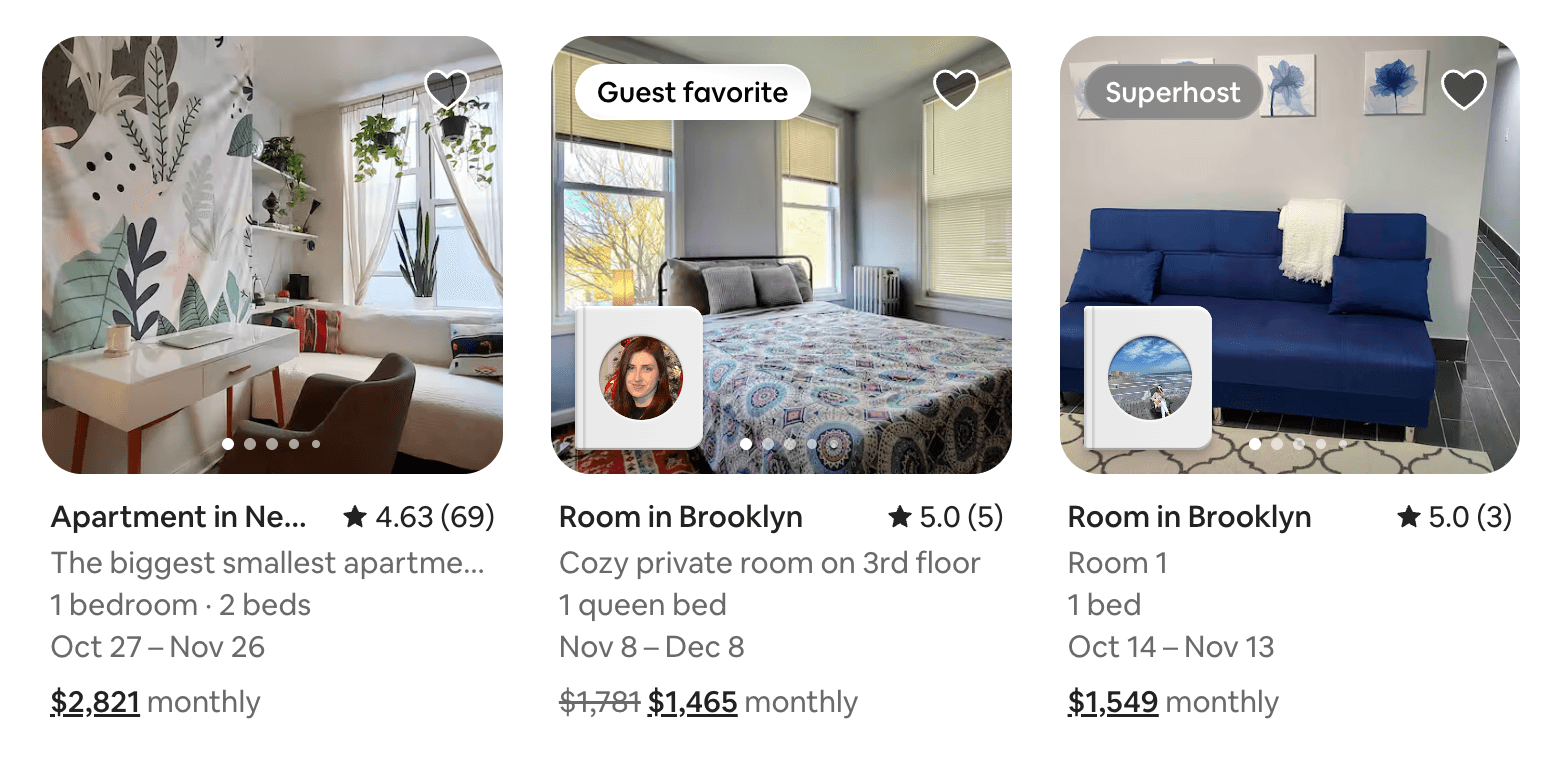

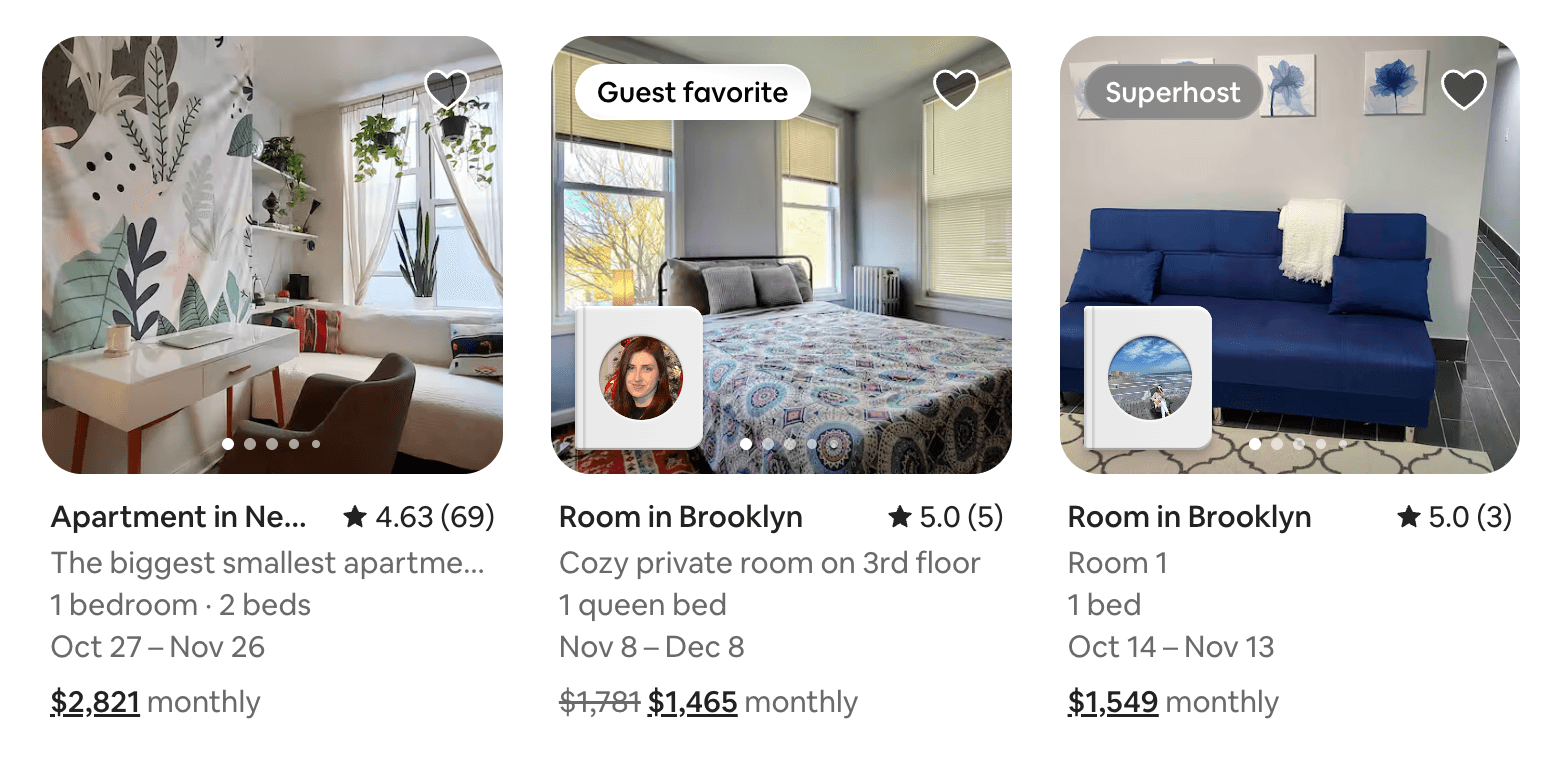

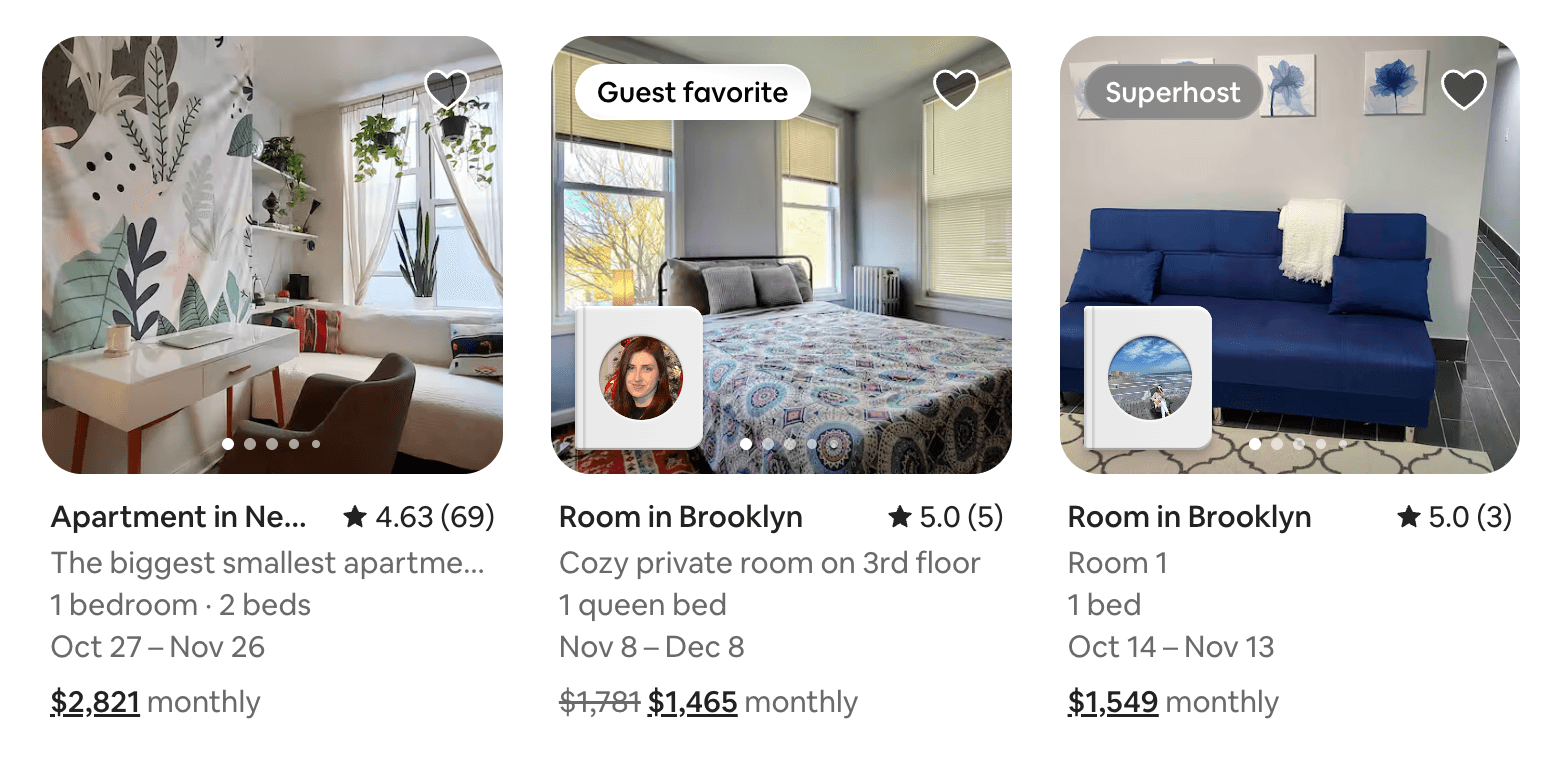

The data that’s available can be displayed on the front end. So for example an Airbnb listing has a photo, name, location, number of beds and bedrooms, avg. rating and number of ratings, etc. And the designer has decided how to display all of this information in a consistent way, and how to handle different data in that space. For example a listing name that’s long, or different color images (see how the heart has a white border so it works on a light or dark background?)

Some other design tips

Not every bit of available data needs to be displayed. Going back to the Airbnb example, there’s hundreds of other data points about those listings that they don’t show on the card. Amenities, the host’s name, specific reviews, etc. They chose to only display the data that mattered when you were browsing a lot of listings.

Not every piece of data needs a label. You probably don’t need to say “Address: 555 North street…” if it’s obvious that it’s an address. ****Things like prices, locations, first and last name, date created, etc. can usually stand on their own without an extra label cluttering the space.

How can I improve handoff?

Work backwards from available data. If you know what data exists and what properties it has, you can design better experiences that actually use that data well. Knowing every piece of data that’s tracked for a user will help you design their profile based on that. Knowing what features different users have access to can help you tailor user experiences for each persona.

Design for different data. Going back to our previous conversations about error states, make sure you know what data could be populating your UI designs. Is there a character limit on the bio that a user can write? If not you probably want to limit how much space it can take up. Are the thumbnail images optional when someone shares a video? Then you need to design what the video card looks like with no image, or a placeholder.

Add documentation notes for backend devs. Front end documentation might seem more important, but clear handoff notes for your backend devs are really helpful too. A lot of times it’s not self-evident from the designs what’s static vs. dynamic based on data (for example a dashboard page might always say “dashboard” as the heading, but the home page might say “welcome back, Henry” based on the user’s name). I find it’s helpful to write in in-context notes in Figma to explain where data is coming from, or when data on the backend should be updated.

Design with real data. Try to avoid lorem ipsum or placeholder content if you can. Use realistic user names, emails, file names, and images (no one posts stock-photo quality images on craigslist). If you don’t already have sample data to pull from AI can be really helpful for this by creating even niche and specific example content to use.

Knowing all of this will make your designs more realistic and effective, and stress testing your designs with real data will make it more likely that your vision makes it through implementation.

Using AI to help with handoff

The elephant in the room: how can I use AI to make this all less of a headache?

Create code prototypes for handoff. You can use a tool like Magicpath, lovable, or v0 to create code prototypes for handoff to help more accurately document your designs, especially for components or interactions like forms that are hard to prototype in Figma. Even better, use Cursor to prototype with the actual context of your codebase.

Use AI to explain code: Whether you’re prototyping or just learning code AI is really good at explaining how code works in plain english. This means you can ask questions in parallel while you’re working, or get help understanding a bug or constraint you’re running into.

Use AI for feedback and ideas. Prompt AI to give you input on what questions your developers might have to make sure you’re covering them. You can share a screenshot of your designs and a brief description with a prompt like "You're a full-stack development expert. What unanswered questions do you have about implementing this feature?"

Generate documentation from Loom transcripts. If you’re already recording a Loom video to document designs you can take the transcript and use it to generate written documentation.

Use it to recommend learning resources: Once you’re diving more into learning code or even just vibe coding you can use web search and deep research mode to explore other courses and tutorials to continue your research.

Experiment with real projects: The best way to learn is to actually try building something. In your free time try to vibe code something like a to-do app and see how it goes. What’s hard to translate from design into code? What doesn’t work the way you expected it to? I can tell you firsthand that actually dipping your toe into development is insanely eye-opening.

The good news is that software development is extremely well documented online, so it’s really well covered in LLM’s training data. Plus these models are specifically trained to know how to code, so there are a lot of ways you can benefit from that expertise.

Where to start tomorrow

This is all great, but where can I actually start diving in with all of this stuff?

Talk to your devs. Reach out, ask for feedback, invite them to design reviews. Handoff is probably confusing for them too, so most of the time they’ll be more than happy to give ideas for how to improve handoff, and join the design process earlier to ask questions.

Learn more about your code component library. It’s really important context to know about the components your dev team is building with, whether you’re getting access to your company’s Github repo, you’re looking through the components in Storybook, or you’re just reading the documentation of the component library they’re using.

Start recording Loom videos for documentation. A good place to start is just recording a Loom video the same way you’d present your designs to anyone. It’s context that the dev team doesn’t usually get, and it can lead to some great questions. Plus it’s all transcribed, so it’s easy to turn into written docs.

Present your designs to AI for feedback. Ask Chatgpt what questions it would want documented if it were a developer. Some things it points out might be easy changes, some might require documentation, and some you might not have the answer to and you’ll have to talk to your devs. But it’s a great way to get out of your bubble and get some new perspective on your designs.

Vibe code an app for yourself. It’s fun, it’s really easy to get started, and it’s extremely eye opening. Plus, best case scenario, you make something cool that’s actually useful.

Wrap-up

All of this to say, code isn’t as scary as it can seem.

And developers aren’t the bad guys.

It can be frustrating when you design something perfect that doesn’t make it into production, but most of the time it’s a communication issue more than anything. If you can learn more about the other side of designer/dev handoff you can help bridge the gap and make sure your good ideas make it to the actual user experience.

Subscribe for more articles like this

A playbook for design to dev handoff

The real user experience happens in code. Here's how to be a part of designing it, and how AI can help

Henry Dan

Oct 14, 2025

The real user experience happens in code, not Figma.

You can spend as much time as you want designing pixel perfect screens and idealized user flows, but if your great ideas don't make it into code your users will never know.

A lot of designers will throw their designs over the wall and hope developers figure it out. But the designers who understand more about development to collaborate effectively are the ones shipping better products, faster.

I'm not saying you need to be an expert developer to design great experiences, you just need to speak their language well enough to be a true collaborator instead of a bottleneck.

This guide will show you how to bridge that gap, from specific tips on where to get started to AI tools you can use to write more code yourself. The goal is to build the kind of designer-developer partnership that leads to exceptional products and deepens your impact as a designer.

Who cares?

Why do I have to learn about development? Can't developers just learn design, or better yet just do what I tell them?

The best solutions are desirable AND feasible. When you can understand and design based on technical constraints, you're part of the solution instead of creating problems for developers to solve after the fact. The goal is to be in charge of the compromise yourself, instead of making someone else make that call.

So, do I need to learn to code?

Well, yes and no.

You need to learn about code, but you don’t need to worry about becoming a full stack developer. Here’s what I recommend:

Minimum tier: learn HTML and CSS. You should be able to build the websites you design. The bad news is this isn't optional anymore. The good news is, it's easier than it's ever been to learn. Start using Framer and build an understanding of how layouts and styles are described in code. It’s just as easy to use as Figma, but it’s production-ready.

Mid tier: Build enough technical knowledge to speak the same language. You need to understand roughly what it takes to build what you're designing so you can collaborate instead of just handing things off and hoping for the best.

Top tier: Build towards being a design engineer. Being able to prototype your own ideas in code and even ship code to production is the best way to become insanely hirable and very unfireable as a designer. It also means you have more of a say in what the end user experience looks like, and more agency when it comes to fixing problems.

The more you know the wider range of projects you can work on, and the more people you can work well with. Building your own ideas or being able to communicate with the person who is is mission-critical to bringing your designs to life.

Where do I start?

Bring Developers Into the Conversation Early. Share work in progress, and ask them to point out red flags and questions about the implementation. These problems are easier to solve early when there’s a dialogue, so invite them into the conversation to get their input.

Stick around after handoff. Sending the Figma link is just the start of implementation, and there’s a million surprises that can happen in the translation from design to code. So check in with your devs, see how things are going, and if there are questions you can answer or changes you can make to simplify the designs. Think of it as a gradual transition where your role ramps down as development ramps up, with neither one hitting zero.

Use AI to help with learning and practice. Use Lovable to build a really simple app, and pick through the code to see how it works and how to make changes. AI can help explain code snippets and architecture, and running into bugs and constraints is a great way to learn.

Learn your company’s design system. Components in code are probably very different from your Figma library, so take a step out of your comfort zone and go to the source. Does your button component have primary, secondary, tertiary styles? Or is it filled, outline, ghost? Maybe you call your select input a dropdown when it’s really a combobox. Knowing what this library looks like will help you a) design based on what exists and b) be more intentional about when you want to add a custom component.

These are the basics, and are a fantastic starting point to be more collaborative with your dev team.

Ready to deeper dive? Here are some other areas to get better at:

Writing handoff documentation

In a perfect world your Figma designs can speak for themselves. But this isn’t a perfect world, and products are complicated. Writing documentation can be a huge boost to communication during handoff.

Your goal is to answer 80-90% of questions before development starts. There will always be surprises, but most questions should be preventable. Never hand-wave important details. Avoid hand-waving and saying “we’ll figure that out later”. Every vague detail creates confusion during implementation.

Write notes in context. Copy in Figjam post its to your design file and add notes in context next to the designs. If your developers have dev mode plans you can use figma’s built in annotation and markup tools.

Make it readable - don’t overdo it. Nobody wants to read a novel of text just to do their job. Quick notes and short Loom videos are best. If you have a lot to write make sure it’s organized and searchable, for example adding a linked table of contents in Notion or Google Docs to navigate around.

What should I document?

Try to cover everything that’s not clearly evident just by looking at the designs or clicking on the prototype.

Be specific about data sources and logic: Don't just show a list of users on a dashboard with a show more button, write something like: "Display first 10 users alphabetically. Show more displays the next 5 in the list.”

Define fallback behaviors: What happens when data is missing? "Show avatar if available, otherwise show initials with a randomized color from our brand palette."

Clarify edge cases: What happens when a user has a really long name? “Truncate text to a single line if it extends past the container.” What if there are zero items in this list? “Display this empty state if there are no search results.”

Specify scope clearly. This is a great dashboard design, but is it customizable or filterable? Are individual charts filterable? “Users can filter data and apply it to the entire dashboard and hide charts, but per-chart filtering is out of scope for now.”

Basically good document just means getting the important stuff out of your head, and tracking it somewhere so the devs can answer most of their questions quickly. And if anything else comes up you can focus your time on solving the big problems, not the boring little things.

Frontend Development

TL:DR; Front end code controls everything users can see and interact with directly in their browser, like layouts, buttons, animations, and forms.

The basics

Let’s start with the simplest possible explanation:

The basics of html/css. Hopefully you’ve had some experience playing around with simple HTML/CSS sites. If not, no worries:

HTML (the Blueprint) Its only job is to define and organize the content. It tells the browser, "This is a headline," "This is a paragraph," "This is an image," and "This is a list of links” to create a basic unstyled skeleton of the page.

CSS (the Designer) styles the content defined by HTML. It tells the browser, "Make all headlines dark blue and use a specific font," "Make all images have a rounded border," or "Arrange the links in a horizontal navigation bar."

The basics of React. Think of React as building a user interface with smart, reusable design components like interactive Lego bricks. It’s like a smarter, more dynamic version of your Figma component library.

React allows you to build a dynamic webpage out of individual components, instead of a static HTML/CSS file that is just a fixed document. Individual "components" (like a search bar, a user profile card, or a button) package their own HTML structure, CSS styles, and JavaScript logic together to make them easier to reuse.

React components have state (a built-in memory). They can remember things, like what a user has typed into a search field or whether a dropdown menu is open or closed, and automatically update the display when that "state" changes. This is what makes modern web apps feel so fast and dynamic.

There’s plenty more that I’m glossing over here, but this is the “in a nutshell” explanation.

How can I improve handoff?

So, what do you need to know about the world of frontend development?

Learn your company’s design system. Like we talked about before, code components are a different animal than Figma components. Knowing what components are available will let you plan your design intentionally around what’s possible today, versus what’s custom and will take more time. Talk to your devs, look at the code, or explore the documentation. If you’re using an existing library like MUI or Shadcn there is publicly available documentation. And for custom components your devs may have their own internal documentation in something like Storybook where you can explore the components.

Learn Framer for web development. Framer is a visual builder for websites that looks and feels just like Figma, but lets you create full functional websites using react. It’s a great way to practice designing within constraints while still having a familiar environment to explore.

Note there are also visual builders for react like Reweb and Plasmic. I haven’t used either of them, but it’s worth exploring.

Get access to your team’s repo and explore. Even if you’re not pushing changes to production, it can be a huge help to just have read-only access your team’s code to poke around and see how things work. This is also a great gateway to making small design fixes in code, like fixing colors, border radius, or spacing issues.

Use AI to explain code: You can use tools like Cursor or Claude code let you highlight code sections and ask for explanations that take into account the full context of your software. Or for small sections of code you can even just copy snippets into Chatgpt to get quick, easy to understand explanations.

You need to understand constraints, even if you can’t write code. When making design decisions you want to be able to plan through the lens of a developer. Will this be hard to implement? How will this UI adapt to changing data onscreen? How will it look on desktop vs. mobile? All of this will make your designs more effective.

Backend Development (Super underrated)

Front end is the part of code you can see, back end is pretty much all of the data that powers it.

Basically every piece of information in your designs is powered by data on the backend, and understanding this will help make your designs more true to life.

The basics

Everything is data:

All of your users

Their preferences and saved information

Their account login information

Their permissions and roles (what different types of users see and can do in the app)

The documents, files, images or whatever things that they upload, create, or share in the app

The properties of those things (like the file name and type and when it was created)

The activities people do in the app that get tracked (i.e. if there’s a timeline of changes to a document)

Data can come from other sources via APIs (for example if addresses are auto completed with Google Maps data. You’re pulling that from Google, not storing all of it yourself)

All of this is tracked in a database and is constantly updated when changes are made. When you search for something and it’s loading that’s when the app is taking time to look through the database for the important data.

Picture a huge excel spreadsheet with all of the information needed to run your app.

That data has types

Numbers are numbers (they can be weird stuff like whole numbers or integers and stuff too)

A string is text (like a user’s name)

Boolean is true or false (like checkboxes)

Enum is a selection from a list of options (think select inputs or radio button lists)

The data that’s available can be displayed on the front end. So for example an Airbnb listing has a photo, name, location, number of beds and bedrooms, avg. rating and number of ratings, etc. And the designer has decided how to display all of this information in a consistent way, and how to handle different data in that space. For example a listing name that’s long, or different color images (see how the heart has a white border so it works on a light or dark background?)

Some other design tips

Not every bit of available data needs to be displayed. Going back to the Airbnb example, there’s hundreds of other data points about those listings that they don’t show on the card. Amenities, the host’s name, specific reviews, etc. They chose to only display the data that mattered when you were browsing a lot of listings.

Not every piece of data needs a label. You probably don’t need to say “Address: 555 North street…” if it’s obvious that it’s an address. ****Things like prices, locations, first and last name, date created, etc. can usually stand on their own without an extra label cluttering the space.

How can I improve handoff?

Work backwards from available data. If you know what data exists and what properties it has, you can design better experiences that actually use that data well. Knowing every piece of data that’s tracked for a user will help you design their profile based on that. Knowing what features different users have access to can help you tailor user experiences for each persona.

Design for different data. Going back to our previous conversations about error states, make sure you know what data could be populating your UI designs. Is there a character limit on the bio that a user can write? If not you probably want to limit how much space it can take up. Are the thumbnail images optional when someone shares a video? Then you need to design what the video card looks like with no image, or a placeholder.

Add documentation notes for backend devs. Front end documentation might seem more important, but clear handoff notes for your backend devs are really helpful too. A lot of times it’s not self-evident from the designs what’s static vs. dynamic based on data (for example a dashboard page might always say “dashboard” as the heading, but the home page might say “welcome back, Henry” based on the user’s name). I find it’s helpful to write in in-context notes in Figma to explain where data is coming from, or when data on the backend should be updated.

Design with real data. Try to avoid lorem ipsum or placeholder content if you can. Use realistic user names, emails, file names, and images (no one posts stock-photo quality images on craigslist). If you don’t already have sample data to pull from AI can be really helpful for this by creating even niche and specific example content to use.

Knowing all of this will make your designs more realistic and effective, and stress testing your designs with real data will make it more likely that your vision makes it through implementation.

Using AI to help with handoff

The elephant in the room: how can I use AI to make this all less of a headache?

Create code prototypes for handoff. You can use a tool like Magicpath, lovable, or v0 to create code prototypes for handoff to help more accurately document your designs, especially for components or interactions like forms that are hard to prototype in Figma. Even better, use Cursor to prototype with the actual context of your codebase.

Use AI to explain code: Whether you’re prototyping or just learning code AI is really good at explaining how code works in plain english. This means you can ask questions in parallel while you’re working, or get help understanding a bug or constraint you’re running into.

Use AI for feedback and ideas. Prompt AI to give you input on what questions your developers might have to make sure you’re covering them. You can share a screenshot of your designs and a brief description with a prompt like "You're a full-stack development expert. What unanswered questions do you have about implementing this feature?"

Generate documentation from Loom transcripts. If you’re already recording a Loom video to document designs you can take the transcript and use it to generate written documentation.

Use it to recommend learning resources: Once you’re diving more into learning code or even just vibe coding you can use web search and deep research mode to explore other courses and tutorials to continue your research.

Experiment with real projects: The best way to learn is to actually try building something. In your free time try to vibe code something like a to-do app and see how it goes. What’s hard to translate from design into code? What doesn’t work the way you expected it to? I can tell you firsthand that actually dipping your toe into development is insanely eye-opening.

The good news is that software development is extremely well documented online, so it’s really well covered in LLM’s training data. Plus these models are specifically trained to know how to code, so there are a lot of ways you can benefit from that expertise.

Where to start tomorrow

This is all great, but where can I actually start diving in with all of this stuff?

Talk to your devs. Reach out, ask for feedback, invite them to design reviews. Handoff is probably confusing for them too, so most of the time they’ll be more than happy to give ideas for how to improve handoff, and join the design process earlier to ask questions.

Learn more about your code component library. It’s really important context to know about the components your dev team is building with, whether you’re getting access to your company’s Github repo, you’re looking through the components in Storybook, or you’re just reading the documentation of the component library they’re using.

Start recording Loom videos for documentation. A good place to start is just recording a Loom video the same way you’d present your designs to anyone. It’s context that the dev team doesn’t usually get, and it can lead to some great questions. Plus it’s all transcribed, so it’s easy to turn into written docs.

Present your designs to AI for feedback. Ask Chatgpt what questions it would want documented if it were a developer. Some things it points out might be easy changes, some might require documentation, and some you might not have the answer to and you’ll have to talk to your devs. But it’s a great way to get out of your bubble and get some new perspective on your designs.

Vibe code an app for yourself. It’s fun, it’s really easy to get started, and it’s extremely eye opening. Plus, best case scenario, you make something cool that’s actually useful.

Wrap-up

All of this to say, code isn’t as scary as it can seem.

And developers aren’t the bad guys.

It can be frustrating when you design something perfect that doesn’t make it into production, but most of the time it’s a communication issue more than anything. If you can learn more about the other side of designer/dev handoff you can help bridge the gap and make sure your good ideas make it to the actual user experience.

Subscribe for more articles like this

A playbook for design to dev handoff

The real user experience happens in code. Here's how to be a part of designing it, and how AI can help

Henry Dan

Oct 14, 2025

The real user experience happens in code, not Figma.

You can spend as much time as you want designing pixel perfect screens and idealized user flows, but if your great ideas don't make it into code your users will never know.

A lot of designers will throw their designs over the wall and hope developers figure it out. But the designers who understand more about development to collaborate effectively are the ones shipping better products, faster.

I'm not saying you need to be an expert developer to design great experiences, you just need to speak their language well enough to be a true collaborator instead of a bottleneck.

This guide will show you how to bridge that gap, from specific tips on where to get started to AI tools you can use to write more code yourself. The goal is to build the kind of designer-developer partnership that leads to exceptional products and deepens your impact as a designer.

Who cares?

Why do I have to learn about development? Can't developers just learn design, or better yet just do what I tell them?

The best solutions are desirable AND feasible. When you can understand and design based on technical constraints, you're part of the solution instead of creating problems for developers to solve after the fact. The goal is to be in charge of the compromise yourself, instead of making someone else make that call.

So, do I need to learn to code?

Well, yes and no.

You need to learn about code, but you don’t need to worry about becoming a full stack developer. Here’s what I recommend:

Minimum tier: learn HTML and CSS. You should be able to build the websites you design. The bad news is this isn't optional anymore. The good news is, it's easier than it's ever been to learn. Start using Framer and build an understanding of how layouts and styles are described in code. It’s just as easy to use as Figma, but it’s production-ready.

Mid tier: Build enough technical knowledge to speak the same language. You need to understand roughly what it takes to build what you're designing so you can collaborate instead of just handing things off and hoping for the best.

Top tier: Build towards being a design engineer. Being able to prototype your own ideas in code and even ship code to production is the best way to become insanely hirable and very unfireable as a designer. It also means you have more of a say in what the end user experience looks like, and more agency when it comes to fixing problems.

The more you know the wider range of projects you can work on, and the more people you can work well with. Building your own ideas or being able to communicate with the person who is is mission-critical to bringing your designs to life.

Where do I start?

Bring Developers Into the Conversation Early. Share work in progress, and ask them to point out red flags and questions about the implementation. These problems are easier to solve early when there’s a dialogue, so invite them into the conversation to get their input.

Stick around after handoff. Sending the Figma link is just the start of implementation, and there’s a million surprises that can happen in the translation from design to code. So check in with your devs, see how things are going, and if there are questions you can answer or changes you can make to simplify the designs. Think of it as a gradual transition where your role ramps down as development ramps up, with neither one hitting zero.

Use AI to help with learning and practice. Use Lovable to build a really simple app, and pick through the code to see how it works and how to make changes. AI can help explain code snippets and architecture, and running into bugs and constraints is a great way to learn.

Learn your company’s design system. Components in code are probably very different from your Figma library, so take a step out of your comfort zone and go to the source. Does your button component have primary, secondary, tertiary styles? Or is it filled, outline, ghost? Maybe you call your select input a dropdown when it’s really a combobox. Knowing what this library looks like will help you a) design based on what exists and b) be more intentional about when you want to add a custom component.

These are the basics, and are a fantastic starting point to be more collaborative with your dev team.

Ready to deeper dive? Here are some other areas to get better at:

Writing handoff documentation

In a perfect world your Figma designs can speak for themselves. But this isn’t a perfect world, and products are complicated. Writing documentation can be a huge boost to communication during handoff.

Your goal is to answer 80-90% of questions before development starts. There will always be surprises, but most questions should be preventable. Never hand-wave important details. Avoid hand-waving and saying “we’ll figure that out later”. Every vague detail creates confusion during implementation.

Write notes in context. Copy in Figjam post its to your design file and add notes in context next to the designs. If your developers have dev mode plans you can use figma’s built in annotation and markup tools.

Make it readable - don’t overdo it. Nobody wants to read a novel of text just to do their job. Quick notes and short Loom videos are best. If you have a lot to write make sure it’s organized and searchable, for example adding a linked table of contents in Notion or Google Docs to navigate around.

What should I document?

Try to cover everything that’s not clearly evident just by looking at the designs or clicking on the prototype.

Be specific about data sources and logic: Don't just show a list of users on a dashboard with a show more button, write something like: "Display first 10 users alphabetically. Show more displays the next 5 in the list.”

Define fallback behaviors: What happens when data is missing? "Show avatar if available, otherwise show initials with a randomized color from our brand palette."

Clarify edge cases: What happens when a user has a really long name? “Truncate text to a single line if it extends past the container.” What if there are zero items in this list? “Display this empty state if there are no search results.”

Specify scope clearly. This is a great dashboard design, but is it customizable or filterable? Are individual charts filterable? “Users can filter data and apply it to the entire dashboard and hide charts, but per-chart filtering is out of scope for now.”

Basically good document just means getting the important stuff out of your head, and tracking it somewhere so the devs can answer most of their questions quickly. And if anything else comes up you can focus your time on solving the big problems, not the boring little things.

Frontend Development

TL:DR; Front end code controls everything users can see and interact with directly in their browser, like layouts, buttons, animations, and forms.

The basics

Let’s start with the simplest possible explanation:

The basics of html/css. Hopefully you’ve had some experience playing around with simple HTML/CSS sites. If not, no worries:

HTML (the Blueprint) Its only job is to define and organize the content. It tells the browser, "This is a headline," "This is a paragraph," "This is an image," and "This is a list of links” to create a basic unstyled skeleton of the page.

CSS (the Designer) styles the content defined by HTML. It tells the browser, "Make all headlines dark blue and use a specific font," "Make all images have a rounded border," or "Arrange the links in a horizontal navigation bar."

The basics of React. Think of React as building a user interface with smart, reusable design components like interactive Lego bricks. It’s like a smarter, more dynamic version of your Figma component library.

React allows you to build a dynamic webpage out of individual components, instead of a static HTML/CSS file that is just a fixed document. Individual "components" (like a search bar, a user profile card, or a button) package their own HTML structure, CSS styles, and JavaScript logic together to make them easier to reuse.

React components have state (a built-in memory). They can remember things, like what a user has typed into a search field or whether a dropdown menu is open or closed, and automatically update the display when that "state" changes. This is what makes modern web apps feel so fast and dynamic.

There’s plenty more that I’m glossing over here, but this is the “in a nutshell” explanation.

How can I improve handoff?

So, what do you need to know about the world of frontend development?

Learn your company’s design system. Like we talked about before, code components are a different animal than Figma components. Knowing what components are available will let you plan your design intentionally around what’s possible today, versus what’s custom and will take more time. Talk to your devs, look at the code, or explore the documentation. If you’re using an existing library like MUI or Shadcn there is publicly available documentation. And for custom components your devs may have their own internal documentation in something like Storybook where you can explore the components.

Learn Framer for web development. Framer is a visual builder for websites that looks and feels just like Figma, but lets you create full functional websites using react. It’s a great way to practice designing within constraints while still having a familiar environment to explore.

Note there are also visual builders for react like Reweb and Plasmic. I haven’t used either of them, but it’s worth exploring.

Get access to your team’s repo and explore. Even if you’re not pushing changes to production, it can be a huge help to just have read-only access your team’s code to poke around and see how things work. This is also a great gateway to making small design fixes in code, like fixing colors, border radius, or spacing issues.

Use AI to explain code: You can use tools like Cursor or Claude code let you highlight code sections and ask for explanations that take into account the full context of your software. Or for small sections of code you can even just copy snippets into Chatgpt to get quick, easy to understand explanations.

You need to understand constraints, even if you can’t write code. When making design decisions you want to be able to plan through the lens of a developer. Will this be hard to implement? How will this UI adapt to changing data onscreen? How will it look on desktop vs. mobile? All of this will make your designs more effective.

Backend Development (Super underrated)

Front end is the part of code you can see, back end is pretty much all of the data that powers it.

Basically every piece of information in your designs is powered by data on the backend, and understanding this will help make your designs more true to life.

The basics

Everything is data:

All of your users

Their preferences and saved information

Their account login information

Their permissions and roles (what different types of users see and can do in the app)

The documents, files, images or whatever things that they upload, create, or share in the app

The properties of those things (like the file name and type and when it was created)

The activities people do in the app that get tracked (i.e. if there’s a timeline of changes to a document)

Data can come from other sources via APIs (for example if addresses are auto completed with Google Maps data. You’re pulling that from Google, not storing all of it yourself)

All of this is tracked in a database and is constantly updated when changes are made. When you search for something and it’s loading that’s when the app is taking time to look through the database for the important data.

Picture a huge excel spreadsheet with all of the information needed to run your app.

That data has types

Numbers are numbers (they can be weird stuff like whole numbers or integers and stuff too)

A string is text (like a user’s name)

Boolean is true or false (like checkboxes)

Enum is a selection from a list of options (think select inputs or radio button lists)

The data that’s available can be displayed on the front end. So for example an Airbnb listing has a photo, name, location, number of beds and bedrooms, avg. rating and number of ratings, etc. And the designer has decided how to display all of this information in a consistent way, and how to handle different data in that space. For example a listing name that’s long, or different color images (see how the heart has a white border so it works on a light or dark background?)

Some other design tips

Not every bit of available data needs to be displayed. Going back to the Airbnb example, there’s hundreds of other data points about those listings that they don’t show on the card. Amenities, the host’s name, specific reviews, etc. They chose to only display the data that mattered when you were browsing a lot of listings.

Not every piece of data needs a label. You probably don’t need to say “Address: 555 North street…” if it’s obvious that it’s an address. ****Things like prices, locations, first and last name, date created, etc. can usually stand on their own without an extra label cluttering the space.

How can I improve handoff?

Work backwards from available data. If you know what data exists and what properties it has, you can design better experiences that actually use that data well. Knowing every piece of data that’s tracked for a user will help you design their profile based on that. Knowing what features different users have access to can help you tailor user experiences for each persona.

Design for different data. Going back to our previous conversations about error states, make sure you know what data could be populating your UI designs. Is there a character limit on the bio that a user can write? If not you probably want to limit how much space it can take up. Are the thumbnail images optional when someone shares a video? Then you need to design what the video card looks like with no image, or a placeholder.

Add documentation notes for backend devs. Front end documentation might seem more important, but clear handoff notes for your backend devs are really helpful too. A lot of times it’s not self-evident from the designs what’s static vs. dynamic based on data (for example a dashboard page might always say “dashboard” as the heading, but the home page might say “welcome back, Henry” based on the user’s name). I find it’s helpful to write in in-context notes in Figma to explain where data is coming from, or when data on the backend should be updated.

Design with real data. Try to avoid lorem ipsum or placeholder content if you can. Use realistic user names, emails, file names, and images (no one posts stock-photo quality images on craigslist). If you don’t already have sample data to pull from AI can be really helpful for this by creating even niche and specific example content to use.

Knowing all of this will make your designs more realistic and effective, and stress testing your designs with real data will make it more likely that your vision makes it through implementation.

Using AI to help with handoff

The elephant in the room: how can I use AI to make this all less of a headache?

Create code prototypes for handoff. You can use a tool like Magicpath, lovable, or v0 to create code prototypes for handoff to help more accurately document your designs, especially for components or interactions like forms that are hard to prototype in Figma. Even better, use Cursor to prototype with the actual context of your codebase.

Use AI to explain code: Whether you’re prototyping or just learning code AI is really good at explaining how code works in plain english. This means you can ask questions in parallel while you’re working, or get help understanding a bug or constraint you’re running into.

Use AI for feedback and ideas. Prompt AI to give you input on what questions your developers might have to make sure you’re covering them. You can share a screenshot of your designs and a brief description with a prompt like "You're a full-stack development expert. What unanswered questions do you have about implementing this feature?"

Generate documentation from Loom transcripts. If you’re already recording a Loom video to document designs you can take the transcript and use it to generate written documentation.

Use it to recommend learning resources: Once you’re diving more into learning code or even just vibe coding you can use web search and deep research mode to explore other courses and tutorials to continue your research.

Experiment with real projects: The best way to learn is to actually try building something. In your free time try to vibe code something like a to-do app and see how it goes. What’s hard to translate from design into code? What doesn’t work the way you expected it to? I can tell you firsthand that actually dipping your toe into development is insanely eye-opening.

The good news is that software development is extremely well documented online, so it’s really well covered in LLM’s training data. Plus these models are specifically trained to know how to code, so there are a lot of ways you can benefit from that expertise.

Where to start tomorrow

This is all great, but where can I actually start diving in with all of this stuff?

Talk to your devs. Reach out, ask for feedback, invite them to design reviews. Handoff is probably confusing for them too, so most of the time they’ll be more than happy to give ideas for how to improve handoff, and join the design process earlier to ask questions.

Learn more about your code component library. It’s really important context to know about the components your dev team is building with, whether you’re getting access to your company’s Github repo, you’re looking through the components in Storybook, or you’re just reading the documentation of the component library they’re using.

Start recording Loom videos for documentation. A good place to start is just recording a Loom video the same way you’d present your designs to anyone. It’s context that the dev team doesn’t usually get, and it can lead to some great questions. Plus it’s all transcribed, so it’s easy to turn into written docs.

Present your designs to AI for feedback. Ask Chatgpt what questions it would want documented if it were a developer. Some things it points out might be easy changes, some might require documentation, and some you might not have the answer to and you’ll have to talk to your devs. But it’s a great way to get out of your bubble and get some new perspective on your designs.

Vibe code an app for yourself. It’s fun, it’s really easy to get started, and it’s extremely eye opening. Plus, best case scenario, you make something cool that’s actually useful.

Wrap-up

All of this to say, code isn’t as scary as it can seem.

And developers aren’t the bad guys.

It can be frustrating when you design something perfect that doesn’t make it into production, but most of the time it’s a communication issue more than anything. If you can learn more about the other side of designer/dev handoff you can help bridge the gap and make sure your good ideas make it to the actual user experience.

Subscribe for more articles like this